Product Design

Prototype Development

ML Exploration

EdTech Experiment

Accessibility

AI/ML

Exploring AI's Role in Accessibility

Identifying the Gap

I noticed a fundamental accessibility barrier in British Sign Language learning. Traditional methods required expensive classes, qualified tutors, and synchronous commitment, creating exclusion rather than inclusion. Existing digital tools relied entirely on passive video watching with no feedback mechanism, leaving learners with no way to know if they were signing correctly and no clear path from understanding to fluency.

This felt like an opportunity to explore how machine learning and AI could contribute directly towards accessibility. Could technology create an interactive learning experience that provides real-time feedback, works autonomously, and serves multiple user groups: Deaf users wanting to teach others, hearing learners discovering BSL, classroom environments, and self-teaching adults?

The challenge was more than technical. Designing for a marginalised community required approaching this as an ethical experiment, ensuring the tool felt supportive and empowering rather than clinical or extractive.

Building and Learning

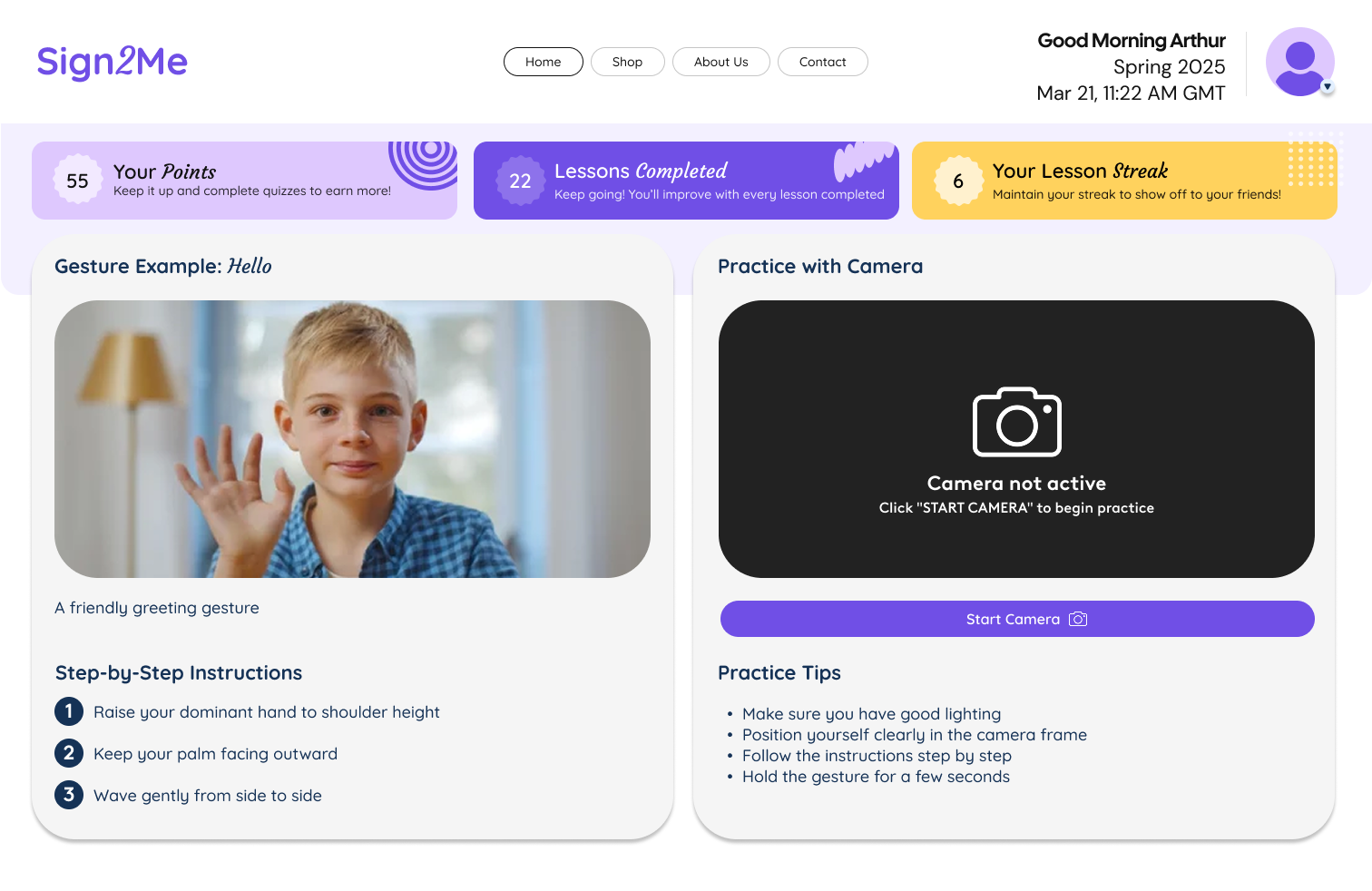

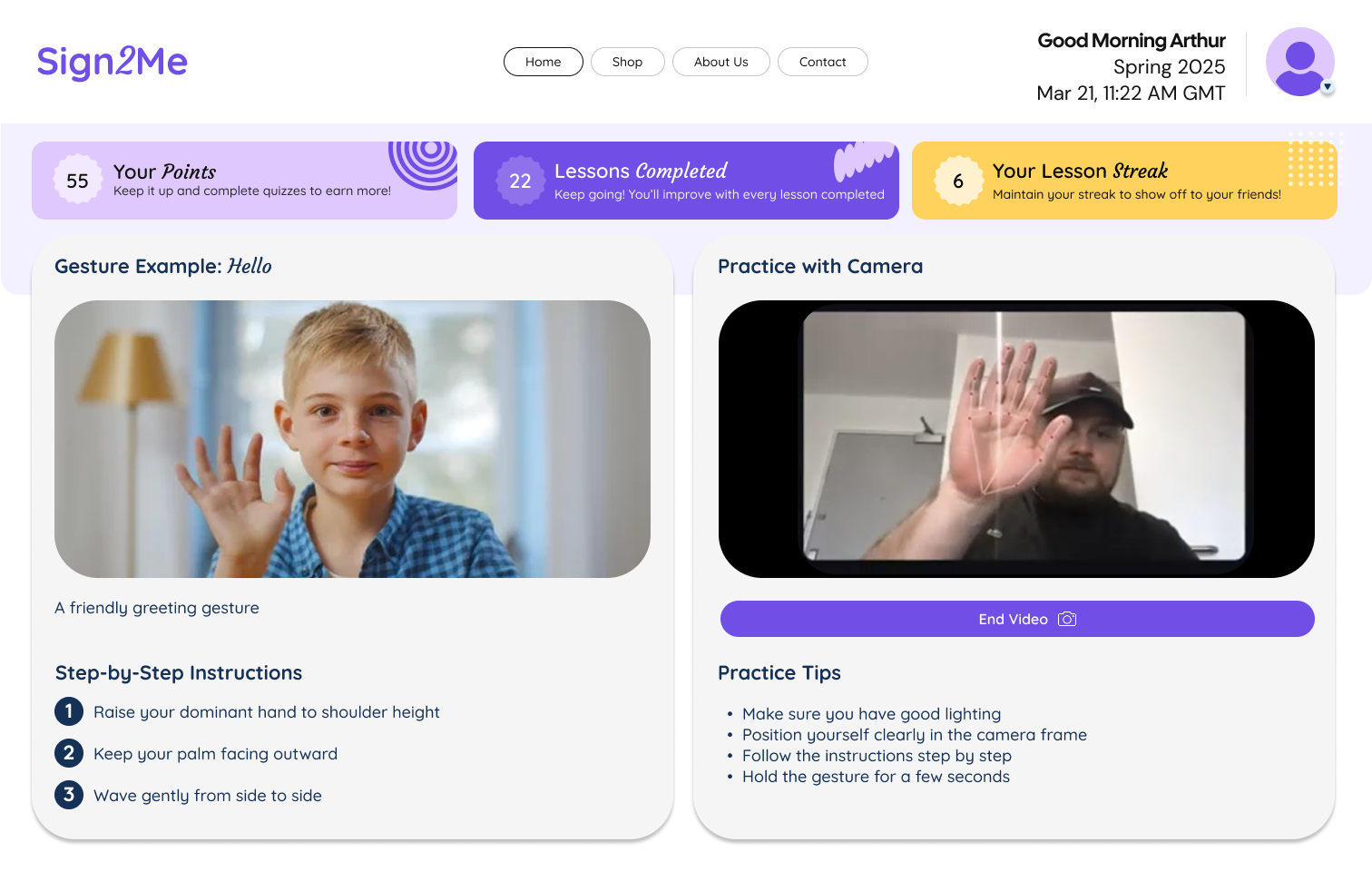

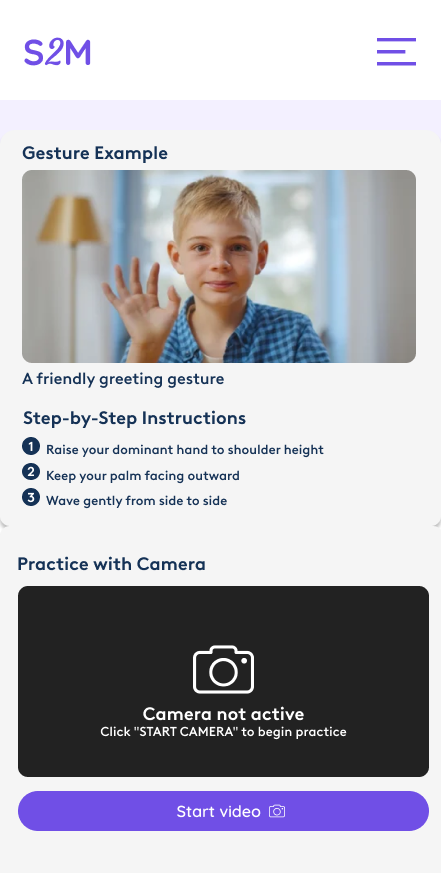

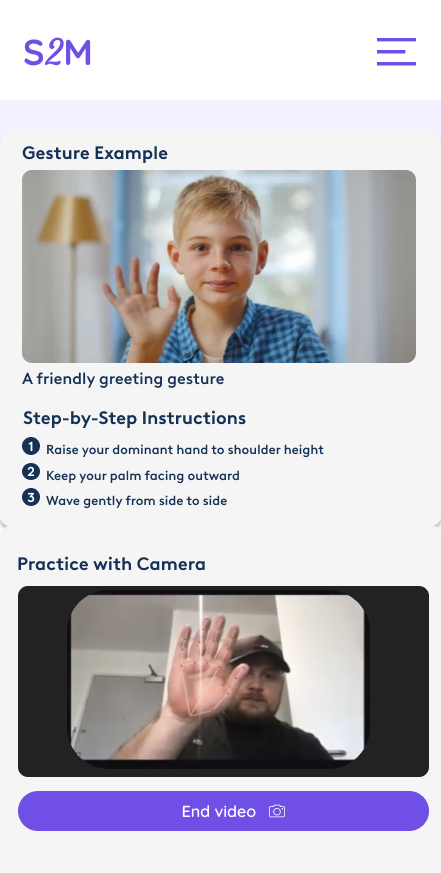

I began a deep dive into how machine learning could enable camera-based sign recognition whilst creating an experience that actually helps people learn. Rather than just designing screens, I built a working prototype myself to understand the technical constraints and possibilities firsthand.

Pedagogical exploration: Instead of implementing pass/fail judgment or static scoring, I experimented with feedback patterns grounded in learning psychology:

1:

"You're close, adjust hand shape"

2:

"Try slowing down"

3:

"Good form, try again"

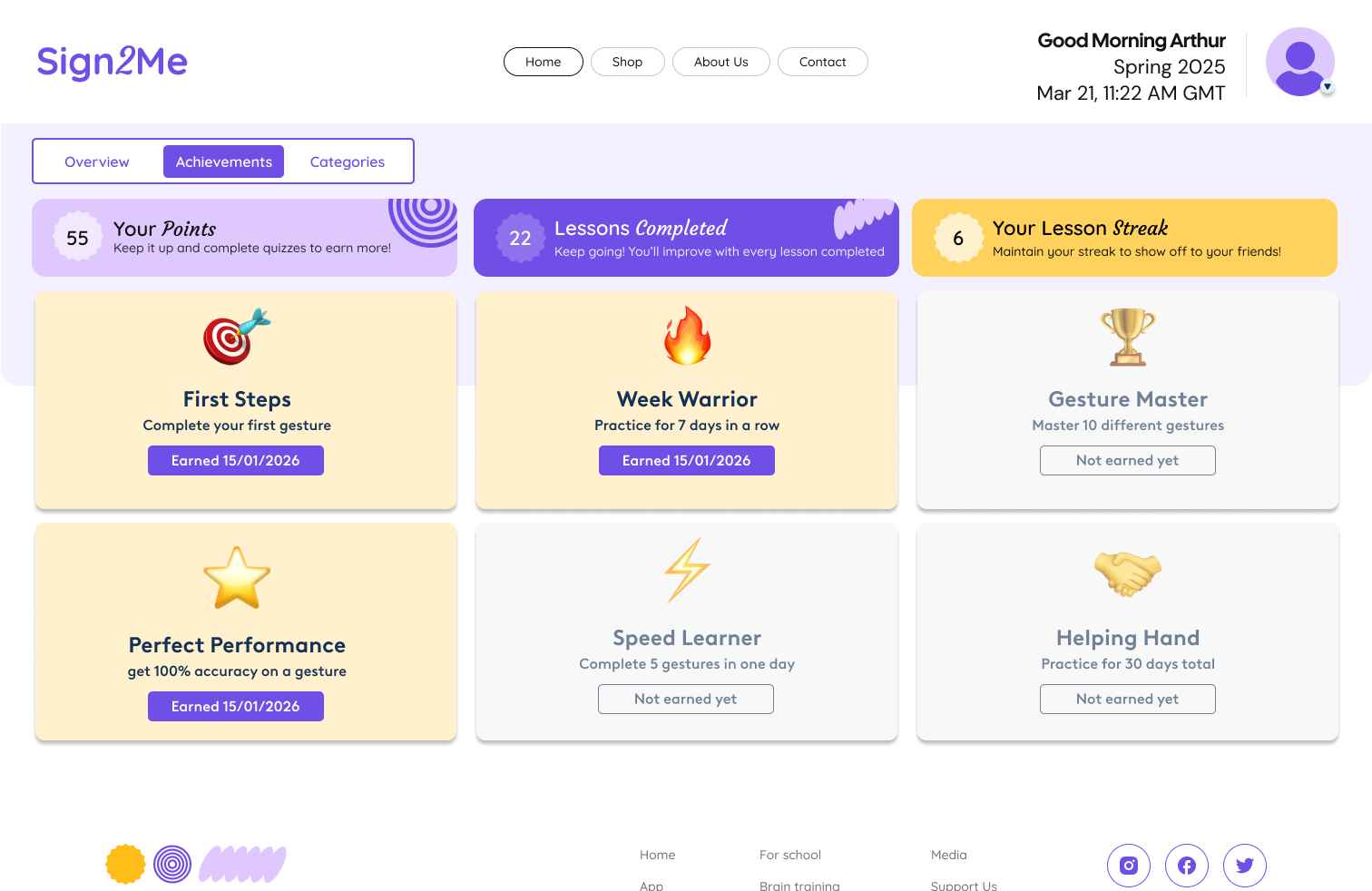

The goal was discovering feedback that remains helpful without discouraging, specific without overwhelming. This became a core design principle rather than an aesthetic choice.

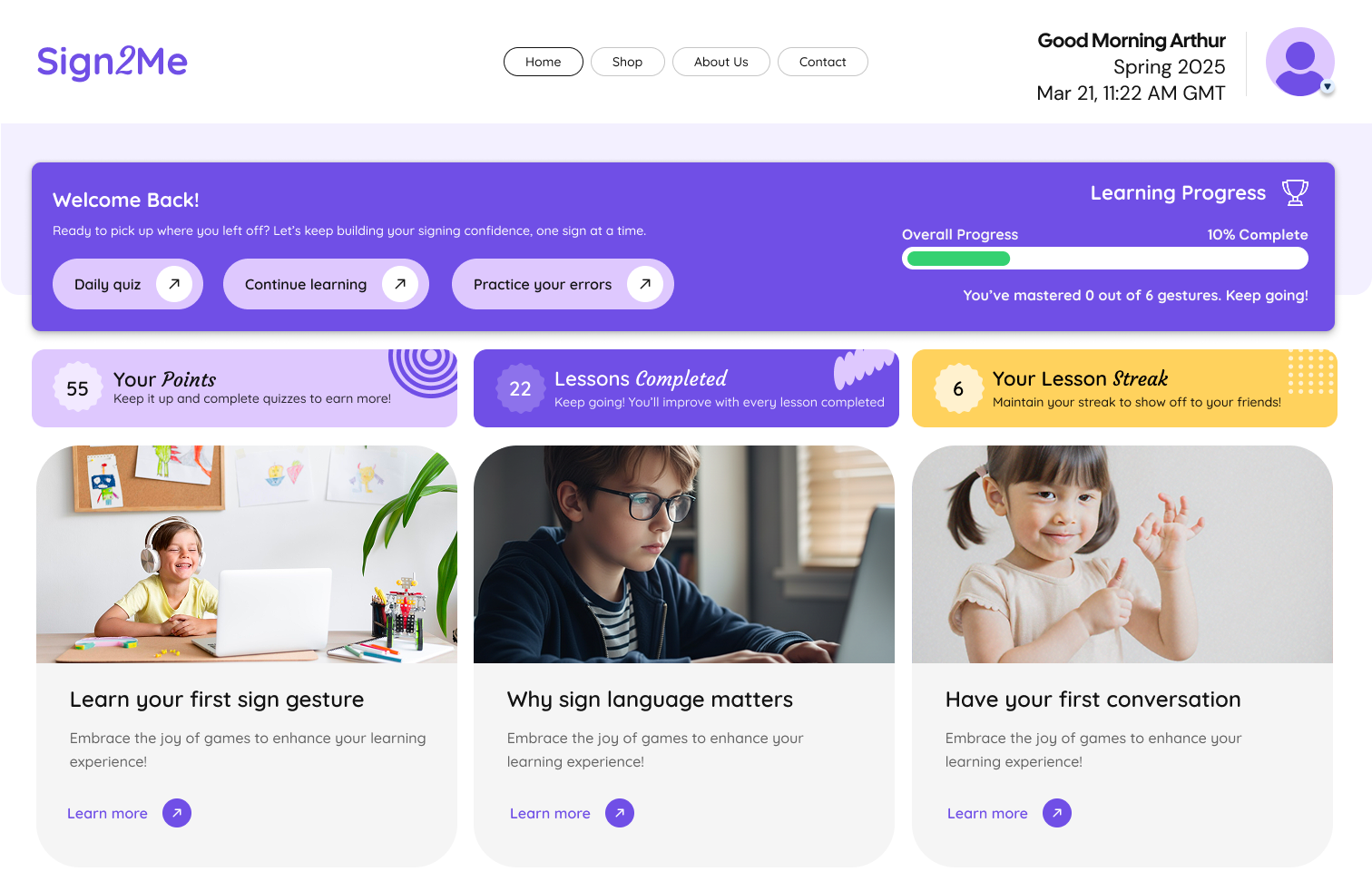

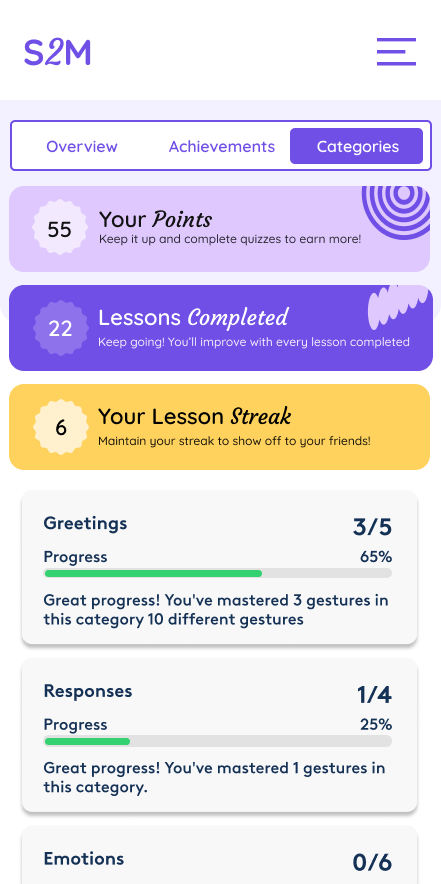

Accessibility as foundation: The system prioritises camera-based input with minimal UI clutter and clear visual hierarchy, deliberately avoiding reliance on heavy text. This approach makes the experience usable across diverse contexts: Deaf users teaching others, hearing learners discovering BSL, classroom environments, and self-teaching adults at home. Genuine inclusive design, not cosmetic accessibility.

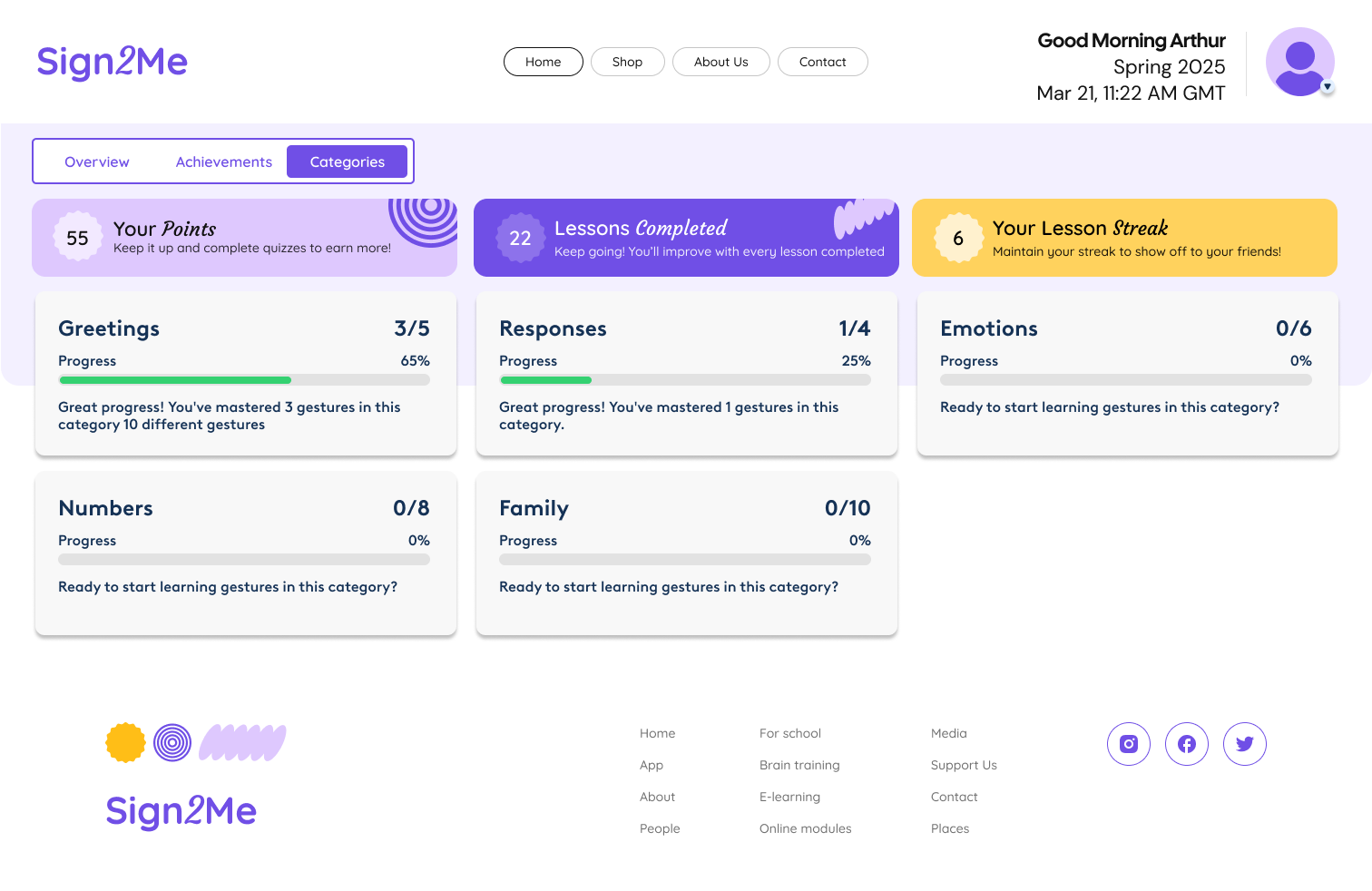

Mapping the learning journey: I structured the experience around distinct practice modes:

1:

Learn mode (introduction to new signs)

2:

Repeat/drill mode (building muscle memory)

3:

Conversational practice (future state for contextual application)

4:

Feedback loops encouraging iteration rather than perfection

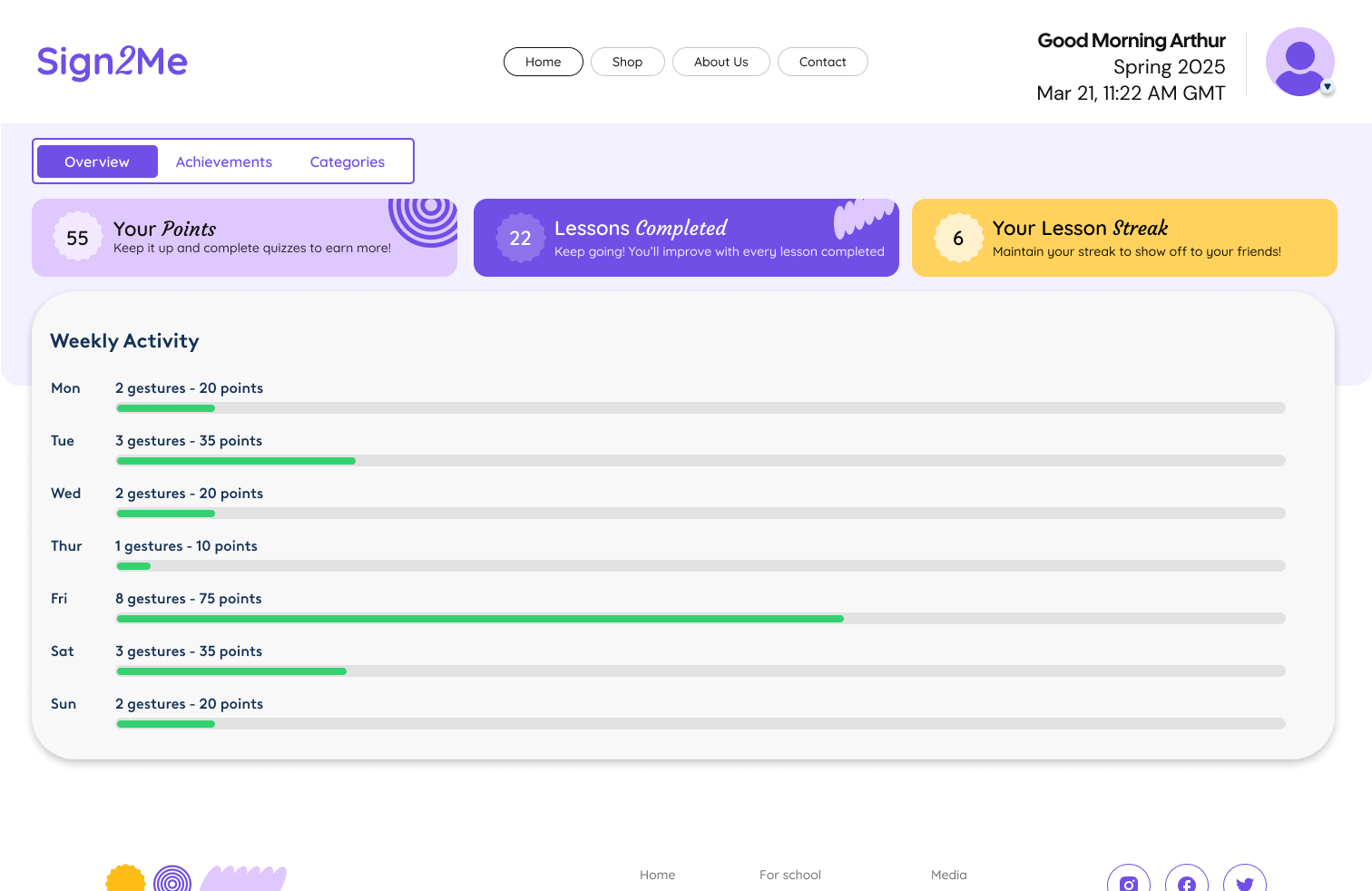

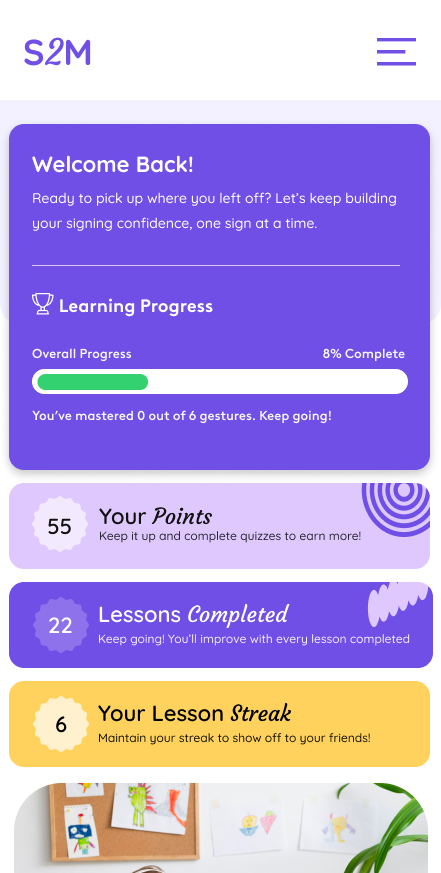

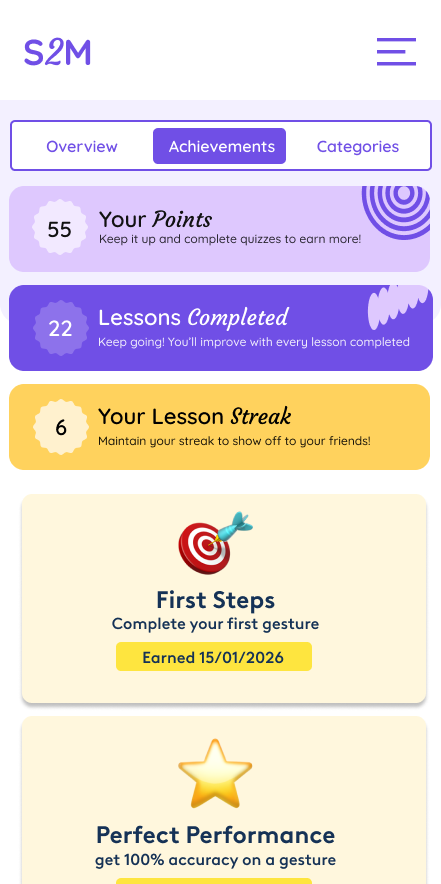

What I built: Complete design system establishing visual identity and interaction patterns. Comprehensive wireframes and user flows mapping the journey from onboarding through progressive skill development. Most importantly, a working prototype I developed myself, demonstrating camera-based sign recognition with real-time feedback mechanics. Building the prototype firsthand gave me direct understanding of technical feasibility and constraints.

Navigating constraints: Working with camera accuracy and latency limitations whilst managing user expectations ("it should just work") taught me about balancing technical reality with ideal user experience. Creating a tool for a marginalised community required constant consideration: this needed to feel supportive, human, and empowering. The ongoing challenge was bridging technical feasibility with inclusive design whilst maintaining ethical responsibility.

Platform thinking: Mobile and tablet-first design allowing hands-free interaction with the camera, designed for one-handed menu navigation whilst keeping both hands visible for signing.